The last Menter Môn Ltd “Ynys Môn Food-Partners” mapping workshop of 2025 had us thinking about food poverty on Anglesey this Christmas.

Our growers, producers and retailers are mapping their own supply/distribution networks, and are optimising their branding “hyper-locally”, communicating some rich and diverse interests (e.g. a map of honey-bee flowers and pollination areas).

But food maps can also provide insights relevant to people in need, mapping social exclusion factors, food access and affordability. These maps can then operationally connect local-food sources, crisis networks, and food surplus resources – a cooperative vision of food equity.

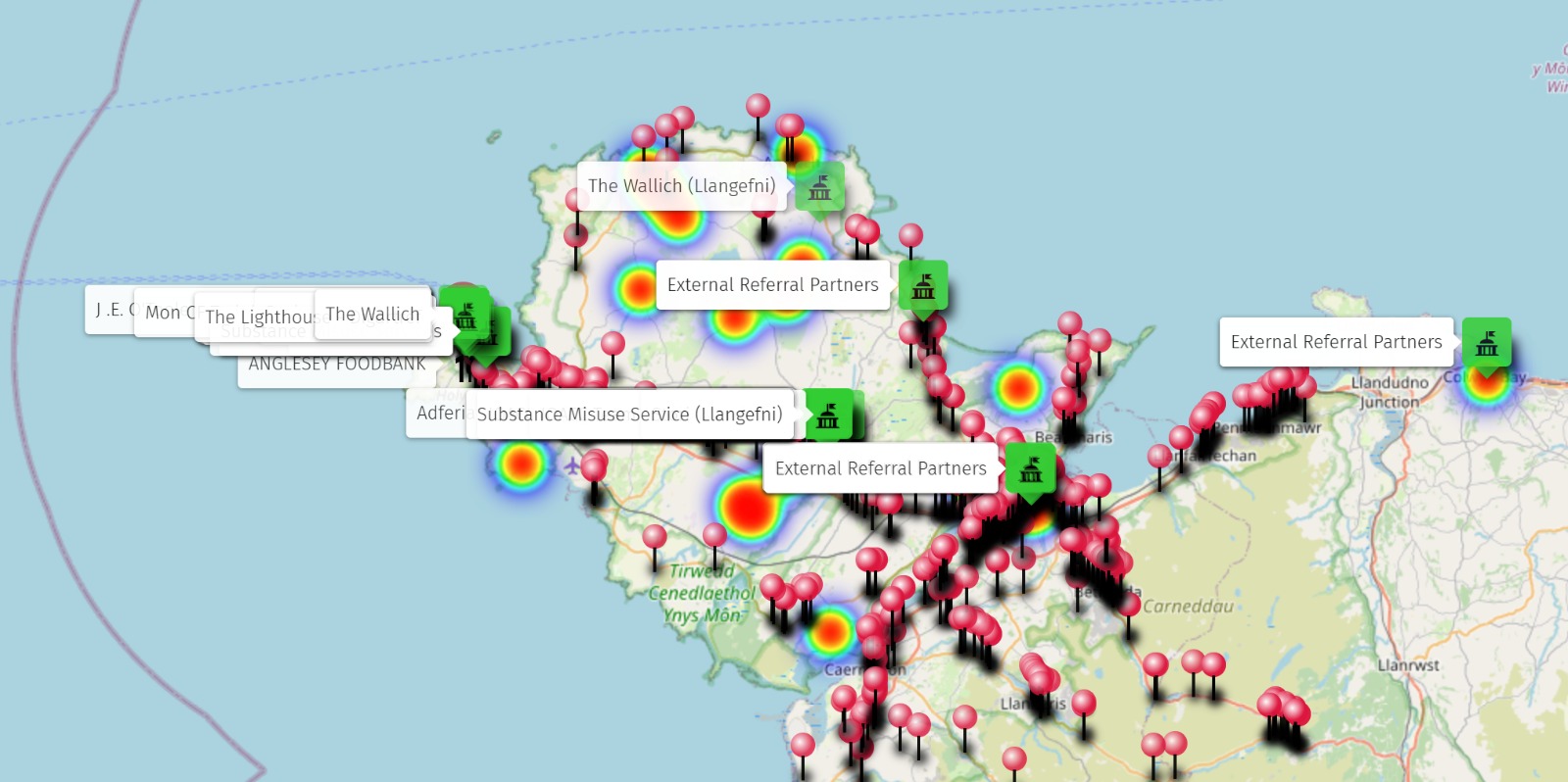

“All the bus stops are the red pins, and the heat map is where we deliver emergency parcels over the last 12 months” says Scott, of Banc Bwyd Môn.

“I am involved with the food bank and tackling destitution together… I have managed to locate all our external partners that offer support advice and aid on the island and refer in to us at the food bank (green icons)… ”

Scott’s “supply-and-demand” map shows us how the needs for food support are concentrated in areas that are far from public transport routes. He explains:

“Key points for the project are the rural areas and the density of emergency aid possibly due to no public transport and lack of shops… paying a higher price due to convenience… that data is so important to provide basic food: and alternatives for those who cannot get to supermarkets and choice…”

Scott’s map displays the locations of fresh food and local businesses alongside information about food accessibility: inclusivity, affordability and equity. Within a few clicks, compelling stories emerge about the effect of public transport on ‘food isolation’, and the need to map informal food networks in a community-owned and inclusive way.

Thanks to Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team for tech support, @UNESCO #geoparks, Rhaglen ARFOR, and @Public Map | Map Cyhoeddus for #osm contributions.

Some partners: Anglesey Bees Melin Llynon Mon Cyngor Anglesey Foodbank Anglesey Fine Foods Bangor University, International

[Read more about OpenStreetMap Food Desert mapping in Wales here:

https://lnkd.in/eagtcM6A]

#opendata #wellbeing #futuregen #autoethnography #missingmaps #foodsecurity #NHS Menter Mon #OSM, #CommunityMapping #gwerintech #fooddeserts #resilience Public Map | Map Cyhoeddus